| Samuel Shimon |

Kika and the Ferrymen

by Samuel Shimon

1

The first time I ever heard the word “wall” I was a kid. It

was in a very sad song that my mother used to sing about a train leaving.

One day I asked her why she always sang such a sad song, and she said

that the young lover was waiting there in the station while the train

carried his loved one far away. He was sad, like a lonely wall, she said.

2

Sitting in the train from London to Newcastle, I was thinking about Hadrian’s

Wall, and found myself little by little remembering the poem by W H Auden,

“Roman Wall Blues”, which is one of only a very few of his

poems translated into Arabic.

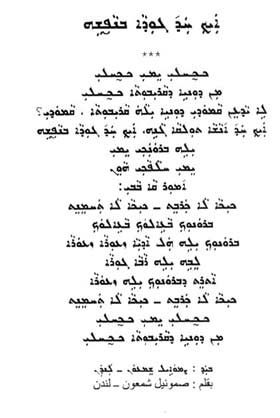

Roman Wall Blues

Over the heather the wet wind blows,

I've lice in my tunic and a cold in my nose.

The rain comes pattering out of the sky,

I'm a Wall soldier, I don't know why.

The mist creeps over the hard grey stone,

My girl's in Tungria; I sleep alone.

Aulus goes hanging around her place,

I don't like his manners, I don't like his face.

Piso's a Christian, he worships a fish;

There'd be no kissing if he had his wish.

She gave me a ring but I diced it away;

I want my girl and I want my pay.

When I'm a veteran with only one eye

I shall do nothing but look at the sky.

W

H Auden

3

Standing at the mouth of the river Tyne, I said to myself: “You

are merely a tourist, jumping from one place to another in this geography

that is completely new to you.” I was standing on ground that was

white with snow, with the squawking of the seagulls mixing with the resonance

of all the new names I was hearing – Tyne, South Shields, Wallsend,

Chollerford, Corbridge, Chesters, Newburn, Northumberland, Hadrian’s

Wall, Arbeia Fort, Brampton, Heddon, Hexham, Hayden Bridge, Vindolanda

Fort . . .

I was eating fish and chips and hearing a voice telling me: “Your ancestors were working here. They were ferrymen from the Tigris.” I was nodding my head and saying, yes, my ancestors were slaves here. Slaves under this same sky.

4

When I say “my ancestors” I can think only of my father. I

don’t like to go further back than him. My father is all my ancestors.

And for me, he is always that deaf-dumb skinny man. He was in his twenties,

my father, when they seized him and threw him into the ship that travelled

from Mesopotamia to Rome, and then from Rome to England, and to South

Shields.

One afternoon I left the Swallow George Hotel and walked over to the bridge at Chollerford. I stood on the bridge remembering my ancestors and I, who had not spoken Assyrian for 30 years, found myself composing a song in my Assyrian/Aramaic mother tongue.

Like a Lonely Wall

I am tired, O Mother. I am tired

of this strange world, I am tired.

I wonder why this world is so strange

Why?

Like a man who lost himself

like a lonely wall

who is your son, O Mother

Mother, I’d die for you

Tell my father

Your boy is still young,

but his heart is bigger than his country

Kika, there’s no need to be sad

no need to worry

Your son loves you

I am tired, O Mother, I am tired

of this strange world, I am tired

like a lonely wall

who is your son, O Mother

5

My father started working as a cook for the ferrymen and the slaves who

worked at the mouth of the Tyne. One day a Roman guard discovered that

they were all eating some strange little pastry things he hadn’t

seen before. “They’re called claicha,” the men told

him. He ate one and found it very delicious. “Where did you get

them from?” he asked, and the ferrymen pointed to the deaf-dumb

skinny man, who smiled back, held up his index finger and put it into

a fist of his other hand. The Roman guard did not understand the gesture,

but later that day, he took Kika to Arbeia Fort to make claicha for the

soldiers and guards.

How did Kika make claicha? Very easily, like this:

Claicha are simply little pastries made with dates. Take some dates and

stone them. Then make dough from wheat flour and oil or butter, some sugar

or honey, a little powdered fennel, a pinch of salt, and a little milk.

Take a small piece of dough and roll it into a ball. Make a finger hole

in it and put in a date. Close it up, and place on a tray. Put the date

balls in a hot oven for ten minutes – until golden brown.

So now the Romans knew why this young cook was so popular with the ferrymen

– he was cooking their own favourite food from back home. One of

the Generals told Kika to make food for him too. He was taken to a big

kitchen with large pantries and all the supplies he could need. However,

he remained there a whole day without doing anything. The General brought

one of the ferrymen over to talk with Kika and explain that he wanted

Kika to be his cook and make meals for him. Kika smiled and nodded.

He took a full bucket of wheat to the miller who crushed it. Back in the

kitchens he set about making burghul kubba and next day surprised the

General with 10 kubbas. This is how he made them:

First, the burghul dough. Burghul are kernels of wheat that have been steamed, dried and crushed, and have been a staple food in Kika’s part of the world since 5,000 BC, and some say 6,000 BC. After the dough, make the spicy, tasty filling.

Use two measures of burghul, one of farina, salt and black pepper, and mix together with some water. Leave for 45 minutes to let the water soak thoroughly into the burghul.

The filling needs two onions, chopped up finely, lamb cut up very small or minced, salt, black pepper, cumin, coriander, and some sliced almonds, all cooked together.

Press or roll out half the dough into the shape of a plate, put the cooked filling onto the dough, leaving a clear edge all round. Press or roll out the other half of the dough into another plate shape and place it over the first one with the meat filling inside. Press the two edges firmly together.

Then cook it in a pan of boiling water for about ten minutes. When

it is ready, lift it out carefully so that it doesn’t break.

One day Kika saw the Romans eating roast chickens, so he decided the next

dish to cook had to be Tashreeb Dijaaj.

For this spicy stew take some chicken, onion, garlic cloves, salt, noomi Basra (dried limes), coriander, curry powder and some chickpeas, a couple of hard-boiled eggs, and some flat bread like pittas.

Skin and clean a whole chicken and cut it into chunks. Peel the onions and cut them into chunks too. Skin a few garlic cloves. Put everything except the eggs into a large pot. Fill the pot half full with water, and when it is boiling skim off the froth. Then let it cook slowly until the chicken is very tender. Add the halved boiled eggs when it is nearly done. The liquid of the stew should be very tasty, like a thick soup or broth.

Now comes the Tashreeb part. Get a large shallow dish, tear the pitta bread into pieces and place on the bottom of the dish. Pour the chicken stew over the bread and let it soak in. Now it’s ready to eat.

Kika became a renowned cook among the Romans, and he stayed with them for years cooking Mesopotamian food. But from time to time he would made strange gestures: he would stroke both cheeks with his hands, point to his breasts with his index fingers, rub both fingers together and point into the distance. How he missed the woman he loved that he had left behind. But it seems nobody understood his gestures and nobody cared to understand. The selfish Romans thought only of their stomachs.

6

I am sitting in the train from Newcastle to London, thinking about the

deaf-dumb cook who spent the rest of his life cooking for the Romans.

I can hear him singing to his love:

Manny merreh leh bayennakh

Manny merreh bit shokinnakh

Atin khayey

Atin Khubby

**

Who said I don’t want you?

Who said I abandoned you?

You are my life.

You are my love.